New houses in the fading sun.

New houses in the fading sun.

Looking forward to taking photos in the rain 🙂

Originally shared by Daniel Swain

“Individual people — on the microscopic scale — always made inventions and discoveries, whether singly or in groups, but these creators could be factored out of the equation, because it was inventions that gave raise to inventions and discoveries that gave rise to discoveries. This acceleration described a parabola that seemed to soar to infinity. A saturation bend in the curve was not caused by other individuals who sought to protect the environment; the curve would bend only where a failure to bend would destroy the biosphere. Invariably it would bend at the critical point, for if technologies for saving or replacing the biosphere did not come to the rescue of the technologies of expansion, the given civilization would enter a crisis to end all crises, i.e., extinction. With no air to breathe, there could be no one to make further discoveries and receive Nobel prizes.” — Stanislaw Lem, “Fiasco”

Originally shared by Unknown

The death of Claudia J. Alexander, a phenomenal woman of science, was totally overlooked by the social media world. WHY IS THAT??!

Well let me educate you just a little bit.

Claudia J. Alexander, a NASA scientist who oversaw the dramatic conclusion of the space agency’s long-lived Galileo mission to Jupiter and managed the United States’ role in the international comet-chasing Rosetta project, died July 11 at Methodist Hospital of Southern California in Arcadia. She was 56.

The cause was breast cancer, said her sister, Suzanne Alexander.

During nearly three decades at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in La Cañada Flintridge, Alexander was known for her research on subjects including solar wind, Jupiter and its moons, and the evolution and inner workings of comets.

She was the last project manager of Galileo, one of the most successful missions for exploring the distant reaches of the solar system. Alexander was leading the mission when scientists orchestrated its death dive into Jupiter’s dense atmosphere in 2003, when the spacecraft finally ran out of fuel after eight years orbiting the giant planet.

Most recently, she was Rosetta’s U.S. project manager, coordinating with the European Space Agency on the orbiter’s journey to rendezvous with the 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko comet as it circles the sun.

Colleagues said Alexander was particularly keen on”I was a pretty lonely girl. I was the only black girl in pretty much an all-white school and spent a lot of time by myself — with my imagination.”- Claudia Alexander engaging the public in space science.

She spearheaded Rosetta’s efforts to involve amateur astronomers through social media and recognize the value of their ground-level observations of the spacecraft’s path toward deep space. In particular, she spurred the creation of a Facebook group where members of the amateur community post comments on their sightings and interact with her and other scientists.

“Claudia’s vision was to engage and empower the amateur community via various social media… a new wrinkle on the concept” of public engagement in NASA’s missions, said Padma A. Yanamandra-Fisher, a senior research scientist with the Space Science Institute who coordinated the outreach.

“I was a pretty lonely girl. I was the only black girl in pretty much an all-white school and spent a lot of time by myself — with my imagination.”- Claudia Alexander

“I was a pretty lonely girl. I was the only black girl in pretty much an all-white school and spent a lot of time by myself — with my imagination.”- Claudia Alexander

“She had a special understanding of how scientific discovery affects us all, and how our greatest achievements are the result of teamwork, which came easily to her,” JPL director Charles Elachi said in a statement. “Her insight into the scientific process will be sorely missed.”

Alexander was born in Vancouver, Canada, on May 30, 1959. She moved to the Silicon Valley with her family when she was 1 and grew up in Santa Clara. Her father, Harold Alexander, was a social worker and her mother, Gaynelle, was a corporate librarian for chip-maker Intel.

As an African American in a predominantly white community, Alexander felt isolated. Writing became a refuge for her.

“I was a pretty lonely girl,” she recalled in a feature for the University of Michigan’s Engineering Magazine. “I was the only black girl in pretty much an all-white school and spent a lot of time by myself — with my imagination.”

She wanted to study journalism at UC Berkeley, but her parents “would only agree to pay for it if I majored in something ‘useful,’ like engineering,” she said in an interview for the Rosetta website.

During college she became an engineering intern at NASA’s Ames Research Center near San Jose. But she found herself drawn to the space facility and visited it as often as she could. Her supervisor eventually arranged for her to intern in the space science division.

She went on to earn a bachelor’s degree in geophysics at UC Berkeley and a master’s in geophysics and space physics at UCLA. At the University of Michigan, she wrote her doctoral thesis on comet thermophysical nuclear modeling and earned a PhD in atmospheric, oceanic and space sciences.

In 1986, she joined JPL as a team member for Galileo, which was still years from launching.

In 2000, she became Rosetta’s U.S. project scientist at the relatively young age of 40.

“She was always looking to improve the project and make things flow better,” said Paul Weissman, an interdisciplinary scientist on Rosetta. “Europeans can be difficult about collaborations. Claudia would get people to open up and work together.”

In 2003, she became Galileo project manager, guiding efforts to destroy the venerable spacecraft to prevent it from accidentally crashing into and contaminating any of Jupiter’s moons.

She had also served as a science coordinator on the Cassini mission to Saturn.

In her spare time, Alexander wrote two books on science for children and mentored young people, especially African American girls. “She wanted children of color to see themselves as scientists,” her sister Suzanne said.

A fan of the steampunk movement in science fiction, Alexander wrote and published short stories in the genre. She wore the Victorian-style clothing associated with steampunk fashion when she taped a TED talk on how to engage youths in math and science. Her lecture will be released later this year.

Alexander was never married and had no children. Besides her mother and sister, she is survived by a brother, David Alexander.

Via Tania Scott on Facebook

Originally shared by annie bodnar

Edward Snowden wins Swedish human rights award for NSA revelations

Whistleblower Edward #Snowden received several standing ovations in the Swedish parliament after being given the Right Livelihood award for his revelations of the scale of state surveillance.

Snowden, who is in exile in Russia, addressed the parliament by video from Moscow. In a symbolic gesture, his family and supporters said no one picked up the award on his behalf in the hope that one day he might be free to travel to Sweden to receive it in person.

The Guardian

Originally shared by Lauren Weinstein

The latest episode of Mr Robot…

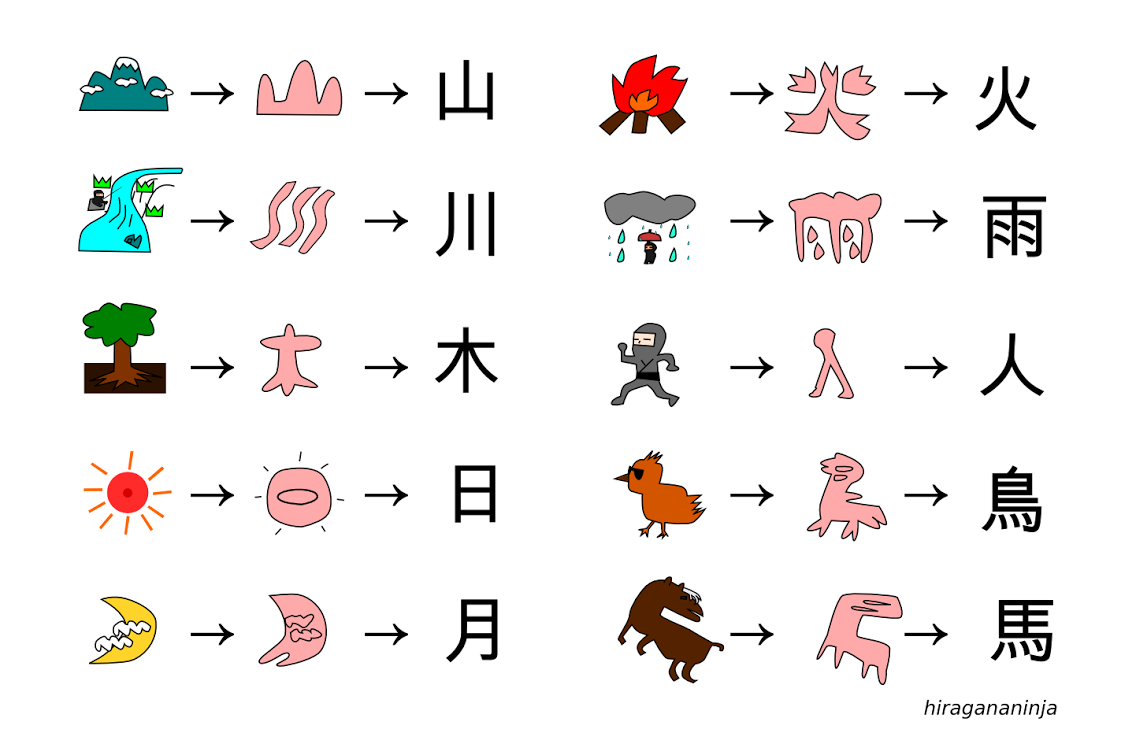

Originally shared by Learn Japanese – HiraganaNinja

How Kanji was made?

Kanji Learning => http://hiragananinja.tk/wp2/80-kanjis-for-beginneers/