Ducks in a row

2020-04-15

Out for a walk, and found a mama duck and babies. This is Crow Canyon Road, a major surface street. Before COVID-19 there would be heavy traffic. But the Samaritan here stopped and shooed them across, and I was able to walk across the road to the center divide to get a picture.

Just around the bend here, on Feb 24, less than two months ago, a 12 year old girl was killed by a hit and run driver. There is a makeshift memorial just out of view.

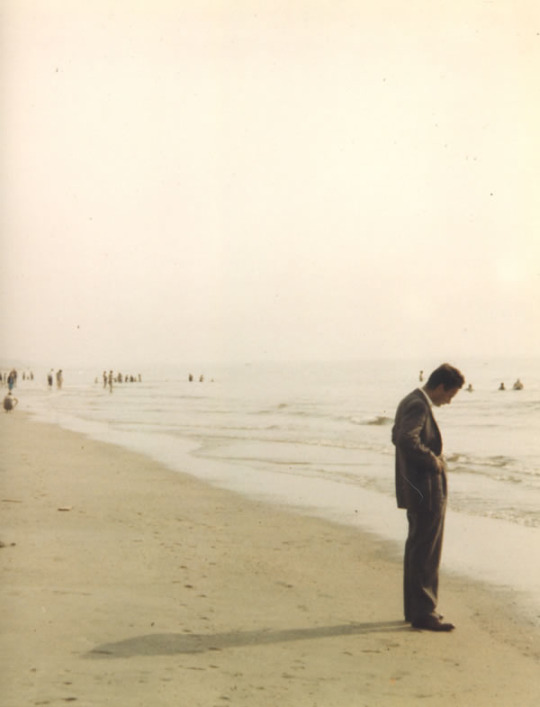

Walking into the sun 2020-03-29

Book collecting as a cargo cult of knowledge

Cargo cult: “A cargo cult is a belief system among members of a relatively undeveloped society in which adherents practice superstitious rituals hoping to bring modern goods supplied by a more technologically advanced society.” Wikipedia

I have a large book collection, more than I can ever read. Yet I still acquire them. Perhaps a hundred recent purchases are stacked next to my bed. This is not rational behavior.

But that’s OK, because I am not a slave to rationality. Instead I am happily practicing the superstitious ritual of buying books in the hope of gaining knowledge without actually doing the work required to learn.

But really, I know I don’t have enough years left in my life to master all the knowledge I desire, and when I die, these books will remain as a tedious chore for someone else, and a sad monument to my failure to learn.

The Bug Apocalypse

Originally shared by Allen Knutson

This is the scariest article I’ve read in a really long, scary, time.

“(It’s easy to read that number as 60 percent less, but it’s sixtyfold less: Where once he caught 473 milligrams of bugs, Lister was now catching just eight milligrams.) “It was, you know, devastating,” Lister told me. But even scarier were the ways the losses were already moving through the ecosystem, with serious declines in the numbers of lizards, birds and frogs. The paper reported “a bottom-up trophic cascade and consequent collapse of the forest food web.” Lister’s inbox quickly filled with messages from other scientists, especially people who study soil invertebrates, telling him they were seeing similarly frightening declines. Even after his dire findings, Lister found the losses shocking: “I didn’t even know about the earthworm crisis!”

Carl Sagan

Carl Sagan, on the meaning of the word “cosmopolitan”, the Library of Alexandria, and the death of Hypatia:

Alexandria was the greatest city the Western world had ever seen. People of all nations came there to live, to trade, to learn. On any given day, its harbors were thronged with merchants, scholars, and tourists. This was a city where Greeks, Egyptians, Arabs, Syrians, Hebrews, Persians, Nubians, Phoenicians, Italians, Gauls, and Iberians exchanged merchandise and ideas.

It is arguably here that the word “cosmopolitan” realized its true meaning — citizen, not just of a nation, but of the Cosmos. To be a citizen of the Cosmos…

Here clearly were the seeds of the modern world. What prevented them from taking root and flourishing? Why instead did the West slumber through a thousand years of darkness until Columbus and Copernicus and their contemporaries rediscovered the work done in Alexandria? I cannot give you a simple answer. But I do know this: there is no record, in the entire history of the Library, that any of its illustrious scientists and scholars ever seriously challenged the political, economic, and religious assumptions of their society. The permanence of the stars was questioned, the justice of slavery was not. Science and learning in general were the preserve of a privileged few. The vast population of the city had not the vaguest notions of the great discoveries taking place within the Library. New findings were not explained or popularized. The research benefited them little. Discoveries in mechanics and steam technology were applied mainly to the perfection of weapons, the encouragement of superstition, the amusement of kings. The scientists never grasped the potential of machines to free people. The great intellectual achievements of antiquity had few immediate practical applications.

Science never captured the imagination of the multitude. There was no counterbalance to stagnation, to pessimism, to the most abject surrenders to mysticism. When, at long last, the mob came to burn the Library down, there was nobody to stop them.

The last scientist who worked in the Library was a mathematician, astronomer, physicist, and head of the Neoplatonic school of philosophy — an extraordinary range of accomplishments for any individual in any age. Her name was Hypatia. She was born in Alexandria in 370. At a time when women had few options and were treated as property, Hypatia moved freely and unselfconsciously through traditional male domains. By all accounts she was a great beauty. She had many suitors but rejected all offers of marriage. The Alexandria of Hypatia’s time — by then long under Roman rule — was a city under grave strain. Slavery had sapped classical civilization of its vitality. The growing Christian Church was consolidating its power and attempting to eradicate pagan influence and culture. Hypatia stood at the epicenter of these mighty social forces. Cyril, the Archbishop of Aleandria, despised her because of her close friendship with the Roman governor, and because she was a symbol of learning and science, which were largely identified by the early Church with paganism. In great personal danger, she continued to teach and publish, until, in the year 415, on her way to work, she was set upon by a fanatical mob of Cyril’s parishioners.

They dragged her from her chariot, tore off her clothes, and, armed with abalone shells, flayed her flesh from her bones. Her remains were burned, her works obliterated, her name forgotten. Cyril was made a saint.

— Carl Sagan, Cosmos

Reflections in a martial arts school…

A number of years ago my wife and I enrolled our daughter in a martial arts school. After watching for a few weeks, we decided to join up as well — “What the heck — seems like a good way to get exercise…” Fifteen years later she no longer goes, but we have progressed to the point where we teach at that same school.

It’s a very kid-friendly place. There are periodic half-day “kids camp” events where a couple of hours are spent teaching martial arts, and a couple of hours are spent playing “ninja games” where they can run and scream and roll around to their hearts content. Parents love these events, because they are usually held near holidays, and it’s cheap daycare.

Recently I was eating a sandwich during the lunch break following a bout of ninja games, looking over 50 kids in random happy groups spread across the mat eating, lunch boxes, paper bags, insulated sacks, soda cans, water bottles, juice boxes, conversation and giggles all over the place. All kinds of crumbs, as well — we have to quickly clean the whole mat before activities can resume.

Sitting there, I’m thinking about how remarkably well all these kids get along, when it suddenly occurs to me that this is a totally integrated scene — asian, black, latino, middle eastern, white, and undetermined in roughly equal portions. It was beautiful, and for a moment I could be proud to be human.

The Value of Science

Originally shared by Corina Marinescu

The Value of Science

Richard Feynman included a poem in his address to the National Academy of Sciences:

I stand at the seashore, alone, and start to think.

There are the rushing waves

mountains of molecules

each stupidly minding its own business

trillions apart

yet forming white surf in unison

Ages on ages

before any eyes could see

year after year

thunderously pounding the shore as now.

For whom, for what?

On a dead planet

with no life to entertain.

Never at rest

tortured by energy

wasted prodigiously by the Sun

poured into space.

A mite makes the sea roar.

Deep in the sea

all molecules repeat

the patterns of one another

till complex new ones are formed.

They make others like themselves

and a new dance starts.

Growing in size and complexity

living things

masses of atoms

DNA, protein

dancing a pattern ever more intricate.

Out of the cradle

onto dry land

here it is standing:

atoms with consciousness;

matter with curiosity.

Stands at the sea,

wonders at wondering: I

a universe of atoms

an atom in the Universe

Source:

http://www.math.ucla.edu/~mwilliams/pdf/feynman.pdf

Photo source:

The death of Claudia J. Alexander

Originally shared by Unknown

The death of Claudia J. Alexander, a phenomenal woman of science, was totally overlooked by the social media world. WHY IS THAT??!

Well let me educate you just a little bit.

Claudia J. Alexander, a NASA scientist who oversaw the dramatic conclusion of the space agency’s long-lived Galileo mission to Jupiter and managed the United States’ role in the international comet-chasing Rosetta project, died July 11 at Methodist Hospital of Southern California in Arcadia. She was 56.

The cause was breast cancer, said her sister, Suzanne Alexander.

During nearly three decades at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in La Cañada Flintridge, Alexander was known for her research on subjects including solar wind, Jupiter and its moons, and the evolution and inner workings of comets.

She was the last project manager of Galileo, one of the most successful missions for exploring the distant reaches of the solar system. Alexander was leading the mission when scientists orchestrated its death dive into Jupiter’s dense atmosphere in 2003, when the spacecraft finally ran out of fuel after eight years orbiting the giant planet.

Most recently, she was Rosetta’s U.S. project manager, coordinating with the European Space Agency on the orbiter’s journey to rendezvous with the 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko comet as it circles the sun.

Colleagues said Alexander was particularly keen on”I was a pretty lonely girl. I was the only black girl in pretty much an all-white school and spent a lot of time by myself — with my imagination.”- Claudia Alexander engaging the public in space science.

She spearheaded Rosetta’s efforts to involve amateur astronomers through social media and recognize the value of their ground-level observations of the spacecraft’s path toward deep space. In particular, she spurred the creation of a Facebook group where members of the amateur community post comments on their sightings and interact with her and other scientists.

“Claudia’s vision was to engage and empower the amateur community via various social media… a new wrinkle on the concept” of public engagement in NASA’s missions, said Padma A. Yanamandra-Fisher, a senior research scientist with the Space Science Institute who coordinated the outreach.

“I was a pretty lonely girl. I was the only black girl in pretty much an all-white school and spent a lot of time by myself — with my imagination.”- Claudia Alexander

“I was a pretty lonely girl. I was the only black girl in pretty much an all-white school and spent a lot of time by myself — with my imagination.”- Claudia Alexander

“She had a special understanding of how scientific discovery affects us all, and how our greatest achievements are the result of teamwork, which came easily to her,” JPL director Charles Elachi said in a statement. “Her insight into the scientific process will be sorely missed.”

Alexander was born in Vancouver, Canada, on May 30, 1959. She moved to the Silicon Valley with her family when she was 1 and grew up in Santa Clara. Her father, Harold Alexander, was a social worker and her mother, Gaynelle, was a corporate librarian for chip-maker Intel.

As an African American in a predominantly white community, Alexander felt isolated. Writing became a refuge for her.

“I was a pretty lonely girl,” she recalled in a feature for the University of Michigan’s Engineering Magazine. “I was the only black girl in pretty much an all-white school and spent a lot of time by myself — with my imagination.”

She wanted to study journalism at UC Berkeley, but her parents “would only agree to pay for it if I majored in something ‘useful,’ like engineering,” she said in an interview for the Rosetta website.

During college she became an engineering intern at NASA’s Ames Research Center near San Jose. But she found herself drawn to the space facility and visited it as often as she could. Her supervisor eventually arranged for her to intern in the space science division.

She went on to earn a bachelor’s degree in geophysics at UC Berkeley and a master’s in geophysics and space physics at UCLA. At the University of Michigan, she wrote her doctoral thesis on comet thermophysical nuclear modeling and earned a PhD in atmospheric, oceanic and space sciences.

In 1986, she joined JPL as a team member for Galileo, which was still years from launching.

In 2000, she became Rosetta’s U.S. project scientist at the relatively young age of 40.

“She was always looking to improve the project and make things flow better,” said Paul Weissman, an interdisciplinary scientist on Rosetta. “Europeans can be difficult about collaborations. Claudia would get people to open up and work together.”

In 2003, she became Galileo project manager, guiding efforts to destroy the venerable spacecraft to prevent it from accidentally crashing into and contaminating any of Jupiter’s moons.

She had also served as a science coordinator on the Cassini mission to Saturn.

In her spare time, Alexander wrote two books on science for children and mentored young people, especially African American girls. “She wanted children of color to see themselves as scientists,” her sister Suzanne said.

A fan of the steampunk movement in science fiction, Alexander wrote and published short stories in the genre. She wore the Victorian-style clothing associated with steampunk fashion when she taped a TED talk on how to engage youths in math and science. Her lecture will be released later this year.

Alexander was never married and had no children. Besides her mother and sister, she is survived by a brother, David Alexander.

Via Tania Scott on Facebook